Toro y Moi, “So Many Details”.

Jessie Ware, “Sweet Talk”.

There are 467 posts filed in Uncategorized (this is page 38 of 47).

Toro y Moi, “So Many Details”.

Jessie Ware, “Sweet Talk”.

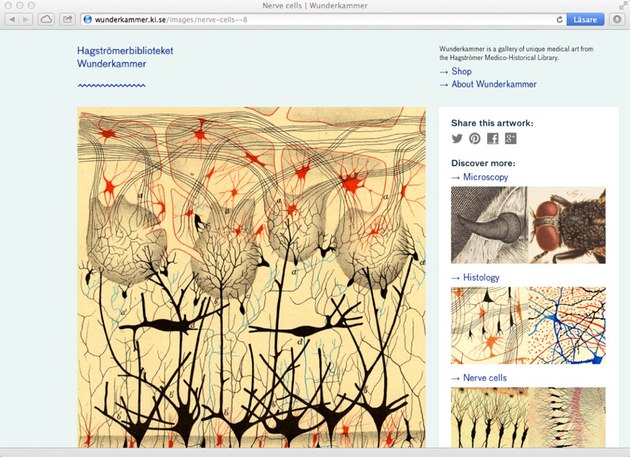

Det medicinhistoriska Hagströmerbiblioteket (nämnt här tidigare) har lanserat en fantastiskt fin webbplats – en Wunderkammer – där man kan utforska en del av de bilder man har i sina samlingar, såsom Ernst Haeckels fladdermöss, Camillo Golgis nervceller eller en man med spetälska. Lätt att gå vilse ett tag, och kanske beställa en plansch.

Ett kort citat från en intervju med Alexis Madrigal, som sammanfattar vad det innebär att vara vad man skulle kunna kalla en kreativ generalist:

I don’t really think of myself as a “technology writer,” I’m just fascinated by technology. If I have advice, it’s that you should use your specialty like frigging X-RAY glasses to see past the superficial stories that other people do about the world. It’s not just about knowing stuff, it’s about using what you know to show people something about the world that they didn’t know before. Some of the best stories for people starting out are to use some bit of specialized knowledge you’ve got (about potato bugs or electrical poles or toilets or Rimbaud) and apply it to something mundane and unexpected. How Potato Bugs Transformed French Poetry Forever! That would kill on the internet.

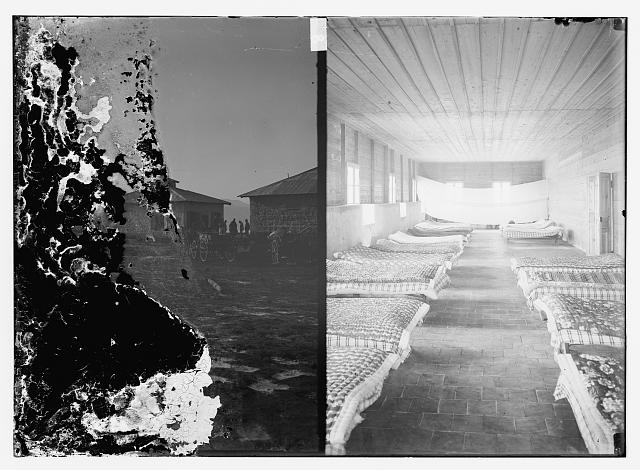

I bara några dagar till pågår en fin liten utställning på Fotografins hus (på Skeppsholmen, ungefär bakom Moderna museet, i Torpedverkstaden) kallad “People next to buildings; Mattresses on floor”. Den består av bilder ur Library of Congress gigantiska fotoarkiv, 44 stycken utvalda av konstnären Johan Hedbäck (som tydligen gått igenom hundratusentals bilder i LoCs arkiv på nätet), många skadade av vatten och svamp, anonyma fotografer, knapphändigt beskrivna, några från amerikanska inbördeskriget, andra från Palestina i början på 1900-talet. De bildar någon slags berättelse.

(Bilden, ovan, som ger namn åt utställningen, hittas här).

Rebecca Mock gör fantastiskt fina animerade gif:ar, som den här:

Som om det inte räckte med en uttömmande J. Robert Oppenheimer-biografi (den prisbelönta American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer) så finns det nu en till, författad av Ray Monk betitlad Inside the Centre: The Life of J Robert Oppenheimer. I en nylig intervju med Monk återberättas följande historia, som väl på något vis ska illustrera Oppenheimers exentriska karaktär:

One day in 1925, J Robert Oppenheimer was travelling in a third-class railway carriage to Southampton. The man who within 20 years would become a central figure in the development of quantum physics and world famous as the so-called “father of the atomic bomb” was trying to read a book on thermodynamics. But he couldn’t concentrate because the couple opposite were having sex. “When the man left,” wrote Oppenheimer’s friend Francis Fergusson, “he [Oppenheimer] kissed the woman. She did not seem unduly surprised. But he was at once overcome with remorse, fell on his knees, his feet sprawling, and with many tears begged her pardon.”

The story that Ray Monk relates in his superb new biography of Oppenheimer doesn’t end there: at Southampton station Oppenheimer was standing on some stairs when he saw the woman below and tried to drop his suitcase on her head. He missed.

På Twitter-kontot @OppieTweets (som ska berätta hans liv i 600 tweets) har man just idag kunna följa detta:

On a train. Trying to read thermodynamics. A couple are having sex. This is awkward. (1925, aged 21)

— Oppenheimer Tweets (@OppieTweets) December 2, 2012

So ashamed. The man left, I got up and kissed the woman. Then I fell to my knees, in remorse, and wept…

— Oppenheimer Tweets (@OppieTweets) December 2, 2012

… And then at Southampton, I confess, I tried to drop a suitcase on her head. What have I become? (1925, aged 21)

— Oppenheimer Tweets (@OppieTweets) December 2, 2012

En fin webbdokumentär om operahuset i Sydney, och en minst lika fin sajt om koreografen och konstnären Rosemary Butcher.

Om du inte känner till scientometri så kan du läsa en kort intervju i The Economist med Samuel Arbesman, författare till boken The Half-Life och Facts, som beskriver det så här:

Put simply, scientometrics is the science of science. It grew out of bibliometrics, the science of books and research papers. In bibliometrics the unit of measurement is a research paper, which are easy to study because you can quantify different aspects of it: who the authors are, who has co-authored papers with those authors, how often a paper is cited, by whom, and so on. […]But bibliometrics is only one subfield of scientometrics. There are all kinds of ways that you can quantify science: you can measure the number of discoveries that are occurring within a particular field, the number of elements in the periodic table, etc. Broadly, scientometrics is about quantifying and understanding how science occurs.

I do think there’s something to be gained from paying attention to aesthetic forebears that lie outside the austere traditions of minimalism and modernism. Perhaps the pendulum is swinging back to a Baroque celebration of diversity of forms, asymmetry, eclecticism and a more poetic sensibility that injects a degree of intuition and randomness into the realms of machine intelligence and digital communication.

Welcome to the coldscape: the unobtrusive architecture of man’s unending struggle against time, distance, and entropy itself.

Adrian Holovaty om sin Soundslice:

Beyond face value, Soundslice is a way of annotating sound. At the moment, it only works on YouTube videos, and the marketing copy focuses on guitar tabs. But really, it’s a general-purpose audio/video annotator. […] I decided to focus on guitar tabs because it was much more easily understood — but I hope people use it for much more than that, inventing uses I never would have thought of.

En fin liten film om formgivarna på Industrial Facility [via: co.DESIGN]:

Jag har ju tjatat en hel del om Robin Sloan här, men jag måste bara få nämna hans roman Mr. Penumbras 24-Hour Bookstore (baserad på en novell publicerad 2009), en riktigt rolig fantasi som nog handlar en hel del om digital humaniora, men också en hel del om den tidiga bokens historia, typografi, “big data”, Ruby och klassisk science fiction. Utan att berätta för mycket kan man ändå säga att artikeln om knäckandet av Copiale-koden som jag länkade till häromdagen, liksom den här artikeln hos Wired om Google Spanner, är högst relevanta.

Berättelsen cirklar en hel del kring minne, bevarande, lager och flöde, något som Sloan tar upp i en intervju med Mother Jones:

MJ: Your book deals a lot with immortality. Do you think things being invented on the internet are in some way not going to withstand time as well as physical literary works?

RS: There’s the challenge of: Is the language and the story strong enough to survive? Things made on the internet today don’t even get to test themselves against that standard because they’re still struggling at the level of compatibility and durability. So I would say right now there is no reason to believe that anything that anyone publishes on the internet will be around in five or ten years.

Now, things are changing really fast. I’m sure in the very early days of books, people were like, “I don’t know, man, I use mine like this, to start the fire.” Books have now matured to the point where they have this durability and they also have time to demonstrate their durability. I would say the internet has done neither. It’s not going to happen on its own. I think it’s really going to take people who have an interest in archiving and in continuity and durability to start to actually maybe redesign the way these things work.

Här kan man förresten höra honom läsa inledningen ur boken: